Flexibility has become a key element in the world of work. Even before the pandemic hit, many jobs were designed to provide greater choice about how, when and where they could be done.

Now the notion of “hybrid working”, which combines time working from home and time in physical proximity to colleagues at a workplace, is expected to be a popular option for many employees as companies seek to attract them back to the office.

Some employers are reducing their office space or even closing locations in anticipation of a long-term switch to hybrid and home working. In countries such as the UK, there has even been discussion of a legal provision of the right to work at home.

But hybrid working is by no means an easy fix. It is unfamiliar to lots of organisations, and could be seen by some as an unsatisfactory compromise. Making it work requires communication and planning on both sides – and an acceptance that things have changed since COVID-19.

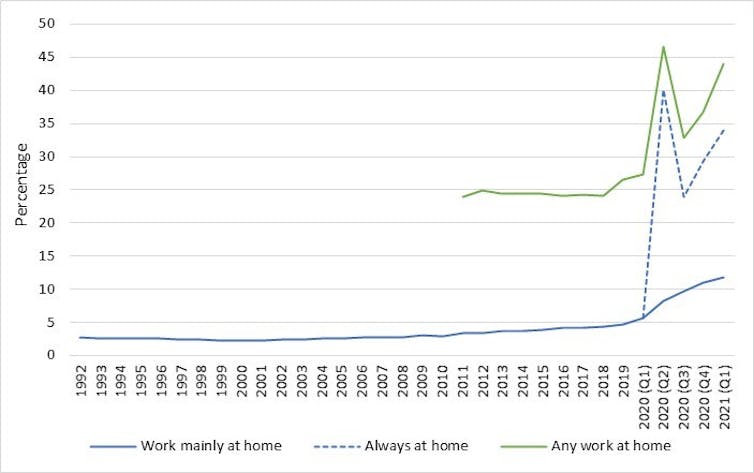

Proportions of workers reporting home as workplace in the UK

As a starting point, research seems to support greater flexibility and its impact on improved work-life balance and productivity (while not forgetting the downsides such as isolation and a blurring between home and work).

Flexibility of this kind can provide staff with greater autonomy, which can significantly enhance wellbeing. However, the relative effectiveness of such schemes is dependent on workloads – often the need to get work done can lead to holidays and time off being interrupted. To this end, the European parliament recently voted for the introduction of a right to not be contactable outside of working hours, which could deliver real benefits to employees.

It’s also important to remember that working from home has not improved work-life balance or leisure time benefits for everyone. Some have encountered more intense patterns of work with reductions in commuting time simply swapped for more time working.

And while some have benefited from greater control over the scheduling of work, others have been subject to high levels of surveillance and heavy workloads.

Evidence also points to difficulties including loneliness, a lack of emotional connection to others, and increases in stress. These effects are important from an employee wellbeing perspective, and also in the wider context of the potential loss of idea sharing, innovation and creativity from not gathering workers together physically.

Best of both?

That said, recent studies suggest a definite preference among many to continue working from home at least some of the time. In one survey of remote workers in Australia, Canada, the UK and US, respondents said their productivity had either remained the same (47%) or increased (35%).

The emerging pandemic evidence suggests that flexibility can deliver a positive outcome for workers, organisations and society, but this is highly dependent on the way it is applied.

For instance, neither working from home or from an office is, by definition, better for employees or employers. Good work can be done at either location. Hybrid models offering time spent in both are likely to be preferred by many people, but again application is key and there is likely to be considerable variation in experience.

Effective hybrid working effectively requires formal flexible working policies to be updated, while recognising that a one-size-fits-all approach rarely actually fits anyone. It is therefore important for employers to make these policies flexible and discuss with employees their preferences and needs, but also for both parties to be realistic about what work can and cannot be done remotely.

It is essential to make sure that both remote and employer workplace locations are properly equipped so that work in any location remains productive. In the medium to longer term, job design can be revisited offering even greater potential for jobs to be approached in flexible ways, including focusing more on delivery of outputs and less on time spent in work or in a particular location.

But it is also true that not all work can be conducted remotely, or all of the time, and that not everyone can or wants to work from home. Organisations should develop policies acknowledging the diverse needs of the workforce and flexibility should be employee-focused wherever possible to create the best outcome for workers, organisations and society.

The Conversation, September 7, 2021